0002 - C++ Attributes

| Status | Accepted |

|---|---|

| Author | |

| Sponsor |

- Planned Version: 202y

Introduction

The C++ 11 ISO standard introduced a standard syntax for attribute annotations which is grammatically unambiguous when annotating a wide variety of language elements. This syntax has become common, recognized and well known, and is an ideal addition to HLSL.

Motivation

HLSL has two syntaxes for specifying source annotations. One, the

Microsoft-style C Attribute syntax, which uses single brackets [] to enclose

an attribute and it’s arguments:

[WaveOpsIncludeHelperLanes]

[shader("compute")]

[numthreads(1,1,1)]

The second, the HLSL annotation syntax, which annotates variable, field and

parameter declarations using a : to separate the name from the specifier:

SamplerState samp1 : register(s5);

Texture2D<float4> text1 : register(t3);

float4 main(float2 a : A) : SV_Target {

...

}

The existing syntaxes in HLSL have limitations. With the introduction of bitfields in HLSL 2021, HLSL semantic syntax on members of a struct or class is syntactically ambiguous with bitfields. Take the following code example:

struct {

uint i : SV_RenderTargetArrayIndex;

}

In this case the syntax is ambiguous with a bitfield declaration, on

encountering the : token the parser must look ahead to see if the next

token is a semantic identifier or an integer constant.

This case is further ambiguous with user-specified semantics where the following code is ambiguous and currently not interpreted as a bitfield declaration:

static int Foo = 1;

struct {

uint i : Foo;

}

If we wish to add source annotations to more grammatical elements in the future

we will encounter more ambiguities because the : character has other meanings

in C and modern C++ as well. to name a few examples: the ternary operator

(condition ? a : b), range-based for syntax (for (variable : collection)),

and switch label marking (case 1:).

We will also encounter ambiguities with the [] syntax. We may encounter issues

with array indexing which valid in contexts where we may wish to annotate

sources in the future. In the future this ambiguity could grow if we incorporate

more C++ features, like lambdas.

Proposed solution

Adopting C++ attributes enables an unambiguous annotation syntax for all the cases where HLSL annotations are supported. Using C++11 attributes the example above can be written as:

struct {

uint i [[hlsl::system_value(RenderTargetArrayIndex)]];

}

Which has no syntactic ambiguity. As in the example above, C++ attributes can also be namespaced, which allows for a clearer delineation of the attribute’s applicability. C++ defines that namespaced attributes not supported by the compiler can be ignored. This enables more robust code sharing in codebases that contain both C++ and HLSL.

Additionally, introducing C++ 11 attributes enables placing attributes on more grammatical constructs in the language. C++ 11 attributes can be applied to statements, declarations and expressions.

Below are a few more examples of C++ attributes that we could support:

struct [[hlsl::layout_attribute]] { // applies to the struct type

int x;

int y;

};

Texture2D<float4> Tex [[hlsl::register(1, 0)]]; // applies to `Tex`;

uint i [[hlsl::system_value(RenderTargetArrayIndex)]]; // applies to `i`.

[[hlsl::system_value(RenderTargetArrayIndex)]] uint j; // applies to `j`.

uint &[[hlsl::address_space(1)]] Ref = ...; // applies to the type `uint &`.

[[hlsl::system_value(Target)]] // applies to the function `fn`.

float3 fn( ) {

[[hlsl::fast]] // applies to the compound expression `{...}`.

{

...

}

float f = [[hlsl::strict]](1.0 * 2.0); // applies to the parenthesis expression `(...)`.

[[hlsl::unroll]] // applies to the for-loop expression.

for (int x = 0; x < 10; ++x) {

...

}

}

Detailed design

The simplest explanation of this feature is supporting C++11 attribute syntax on all shared grammar elements between HLSL and C++. This spec attempts to detail some of the grammar and parsing implications and will specify the process by which existing attributes will convert to C++ attributes.

Attribute Parsing

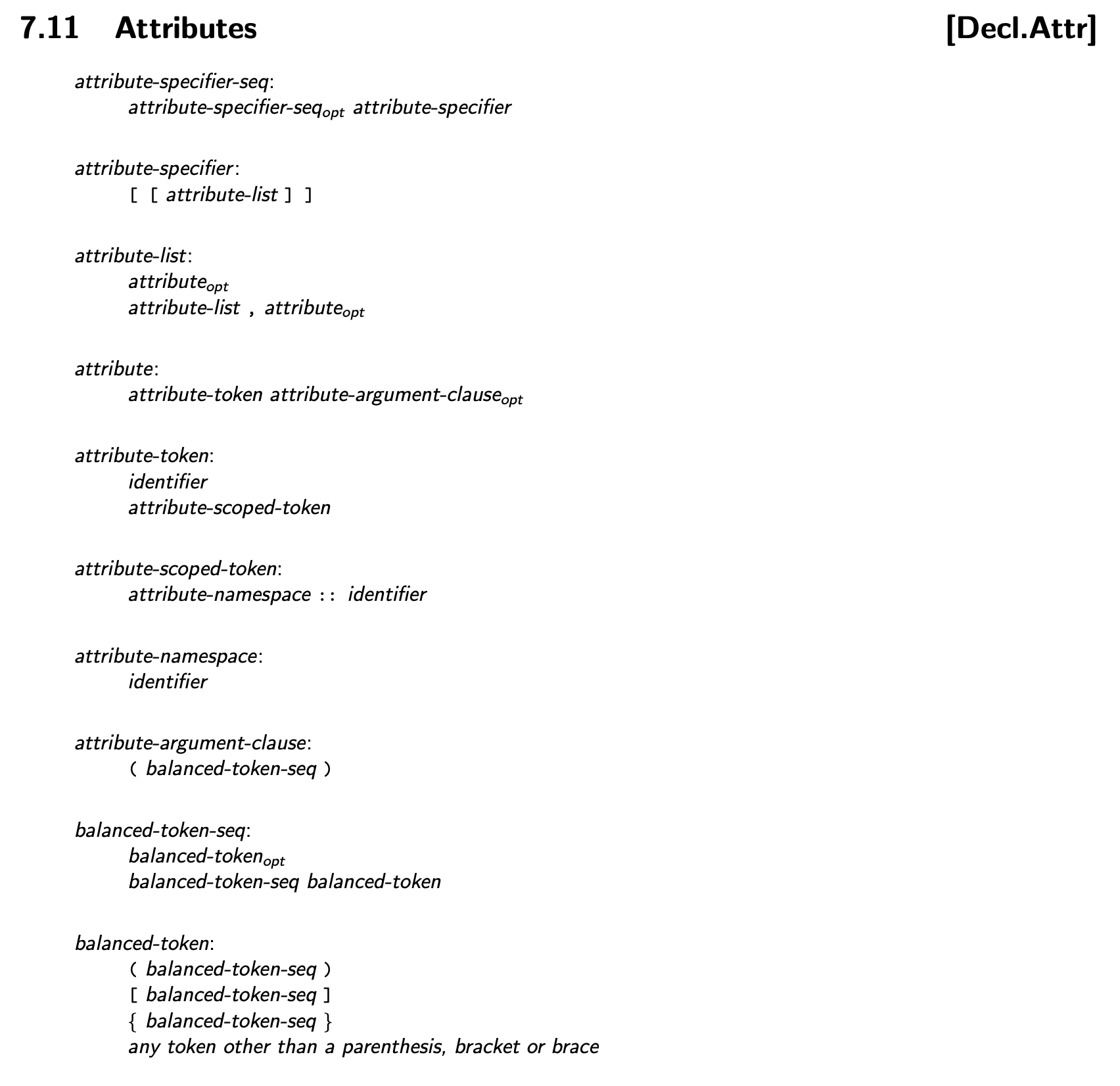

This proposal introduces grammar formulations for parsing attributes matching

some formulations from C++ dcl.attr.grammar. Specifically:

\begin{grammar}

\define{attribute-specifier-seq}\br

\opt{attribute-specifier-seq} \textit{attribute-specifier}\br

\define{attribute-specifier}\br

\terminal{[ [} \textit{attribute-list} \terminal{] ]}\br

\define{attribute-list}\br

\opt{attribute}\br

\textit{attribute-list} \terminal{,} \opt{attribute}\br

\define{attribute}\br

\textit{attribute-token} \opt{attribute-argument-clause}\br

\define{attribute-token}\br

\textit{identifier}\br

\textit{attribute-scoped-token}\br

\define{attribute-scoped-token}\br

\textit{attribute-namespace} \terminal{::} \textit{identifier}\br

\define{attribute-namespace}\br

\textit{identifier}\br

\define{attribute-argument-clause}\br

\terminal{(} \textit{balanced-token-seq} \terminal{)}\br

\define{balanced-token-seq}\br

\opt{balanced-token}\br

\textit{balanced-token-seq} \textit{balanced-token}\br

\define{balanced-token}\br

\terminal{(} \textit{balanced-token-seq} \terminal{)}\br

\terminal{[} \textit{balanced-token-seq} \terminal{]}\br

\terminal{\{} \textit{balanced-token-seq} \terminal{\}}\br

any token other than a parenthesis, bracket or brace\br

\end{grammar}

In contrast to existing HLSL annotations and Microsoft-style attributes, these formulations use case-sensitive identifier tokens

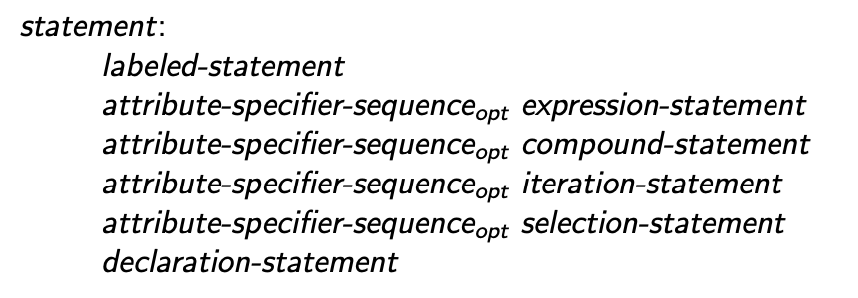

Statements

Note: This is already reflected in the language specification.

\begin{grammar}

\define{statement}\br

labeled-statement\br

\opt{attribute-specifier-sequence} expression-statement\br

\opt{attribute-specifier-sequence} compound-statement\br

\opt{attribute-specifier-sequence} iteration-statement\br

\opt{attribute-specifier-sequence} selection-statement\br

declaration-statement

\end{grammar}

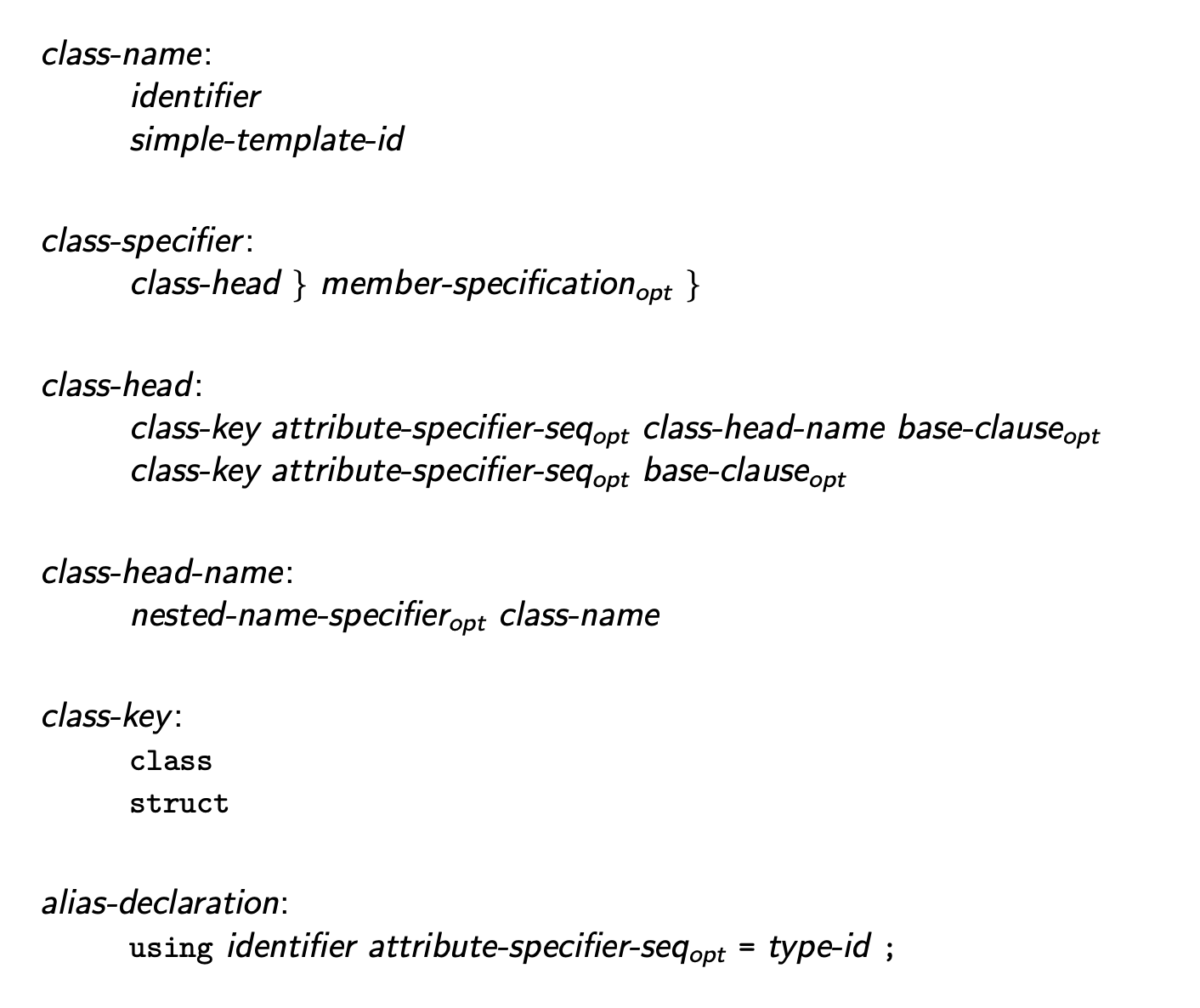

Declarations

The attribute-specifier-seq element supports annotating type declarations. The

following grammar formulations are valid:

\begin{grammar}

\define{class-name}\br

\textit{identifier}\br

\textit{simple-template-id}\br

\define{class-specifier}\br

\textit{class-head} \terminal{\{} \opt{member-specification} \terminal{\}}\br

\define{class-head}\br

\textit{class-key} \opt{attribute-specifier-seq} \textit{class-head-name} \opt{base-clause}\br

\textit{class-key} \opt{attribute-specifier-seq} \opt{base-clause}\br

\define{class-head-name}\br

\opt{nested-name-specifier} \textit{class-name}\br

\define{class-key}\br

\terminal{class}\br

\terminal{struct}\br

\define{alias-declaration}\br

\terminal{using} \textit{identifier} \opt{attribute-specifier-seq} \terminal{=} \textit{type-id} \terminal{;}\br

\end{grammar}

Attribute Specification Language

Attributes annotate source constructs with information. An attribute is said to be applied to the entity or statement identified by the source construct.

Some attributes may be required by an implementation for correct code generation, others may be optionally ignored. An implementation must issue a diagnostic on all ignored attributes unless otherwise specified by the definition of the attribute behavior.

Note: an example here would be optimization hint attributes which an implementation is allowed to ignore without diagnosing.

Each attribute may define specific behavior for how its arguments are parsed. Attributes that do not define custom parsing behavior shall be parsed according to the general rules outlined here.

Note: The clause above enables attributes like the clang availability attribute which supports named parameters (e.g.

[[clang::availability(shadermodel, introduced=6.3)]]), HLSL has a use for similar functionality.

An empty attribute specifier has no effect. The order in which attributes applied to the same source construct are written shall not be significant. When parsing attributes any token that satisfies the requirements of an identifier shall be treated as an identifier even if it has alternate meaning outside the attribute (e.g. keywords). Name lookup is not performed on identifiers within attribute-token. The attribute-token refers to the attribute being parsed, which determines requirements for parsing the optional attribute-argument-clause.

If an attribute is applied to an entity or statement for which the attribute is not allowed to be applied, the program is ill-formed.

The behavior of attribute-token not specified in this specification is implementation-defined.

Two consecutive square bracket tokens shall only appear when introducing an attribute-specifier. Any other occurrence of two consecutive square brackets is ill-formed.

Removal of HLSL Annotation Syntax

With the introduction of C++ attribute syntax the HLSL annotation syntax will be removed from the language. In Clang, C++ attribute syntax can be supported in both HLSL 202x and 202y language modes with deprecation warnings reported for the old HLSL annotation syntax, including fix-it and rewriting tool support in Clang. This will allow easier migration of code from HLSL 202x to 202y. This feature will not be supported in DXC.

The following new attributes are introduced to replace HLSL annotations. These attribute formations are not final and may change as the proposal moves through implementation.

hlsl::user_value(string[, int=0])

The new hlsl::user_value attribute replaces user-defined semantics. The first

argument to the attribute is a string which can contain any valid C-string. The

second optional value is an index.

Consider the following valid HLSL:

struct VSOutput {

float2 TexCoord : TEXCOORD;

};

float4 main(VSOutput input) : SV_TARGET {

return input.xyxy;

}

Under HLSL 202y this code will be rewritten as:

struct VSOutput {

float2 TexCoord [[hlsl::user_value("TEXCOORD")]];

};

float4 main(VSOutput input) : [[hlsl::system_value(SV_Target)]] {

return input.xyxy;

}

hlsl::system_value(enum[, int=0])

The new hlsl::system_value attribute replaces system value semantics. The

first argument is an enumeration which specifies which system value is being

bound, and the second optional value is an index.

Consider the following valid HLSL:

float4 main( float4 p : SV_Position ) : SV_Target2 {

return p;

}

Under HLSL 202y this code will be rewritten as:

float4 main(float4 p [[hlsl::system_value(SV_Position)]]) [[hlsl::system_value(SV_Target, 2)]] {

return p;

}

hlsl::packoffset(int[, int=0])

The new hlsl::packoffset attribute replaces the packoffset HLSL annotation.

The attribute takes one required and one optional integer arguments. The second

integer must be greater than or equal to 0 and less than or equal to 3.

The first value specifies the starting row for packing data, and the second

value specifies the starting column. Existing packoffset arguments written

c<row>.<column_letter> map to the new attribute as hlsl::packoffset(<row>, <column_index>), where <column_index> maps as in the table below.

| column_letter | column_index |

|---|---|

| x | 0 |

| y | 1 |

| z | 2 |

| w | 3 |

Consider the following valid HLSL:

cbuffer CB {

float2 g1 : packoffset(c1);

float2 g2 : packoffset(c1.z);

}

Under HLSL 202y this code will be rewritten as:

cbuffer CB {

float2 g1 [[hlsl::packoffset(1)]];

float2 g2 [[hlsl::packoffset(1, 2)]];

}

hlsl::binding(int[, int=0])

The new hlsl::binding attribute replaces the register HLSL annotation. The

attribute takes one required and one optional integer arguments. The first

integer argument specifies the binding index. the second integer specifies

the binding scope of the binding index. The interpretation of this attribute is

defined by the target runtime’s binding model.

In DirectX, the first value maps as the register value, and the second the register space. DirectX scopes bindings by resource class, allowing the same register and space assignments to be specified for resources of different types (e.g. a UAV and SRV may have the same register and space values without aliasing).

In Vulkan, the first value maps as the binding index, and the second maps as the descriptor set index.

Consider the following valid HLSL:

SamplerState samp1 : register(s5);

Texture2D tex1 : register(t0, space3);

RWByteAddressBuffer buf1 : register(u4, space1);

Under HLSL 202y this code will be rewritten as:

SamplerState samp1 [[hlsl::binding(5)]];

Texture2D tex1 [[hlsl::binding(0, 3)]];

RWByteAddressBuffer buf1 [[hlsl::binding(4, 1)]];

hlsl::payload_access(, …)

The new hlsl::payload_access attribute replaces the read and write HLSL

annotations for raytracing payload access qualifiers. The attribute takes an

enum value specifying read or write to denote the type of access and a

variable argument list of enumeration values specifying the stage that the

access qualifier applies to. Consider the following currently valid HLSL:

struct [raypayload] Payload {

float f : read(caller, anyhit) : write(caller, anyhit);

};

Under HLSL 202y this code will be rewritten as:

using namespace hlsl;

struct [[raypayload]] Payload {

float f [[payload_access(read, caller, anyhit), payload_access(write, caller, anyhit)]];

};