ReactXP was developed by the Skype team at Microsoft as a way to improve development agility and efficiency. In this article, I’ll talk more about the architecture of the new Skype app.

Implementing Stores with ReSub

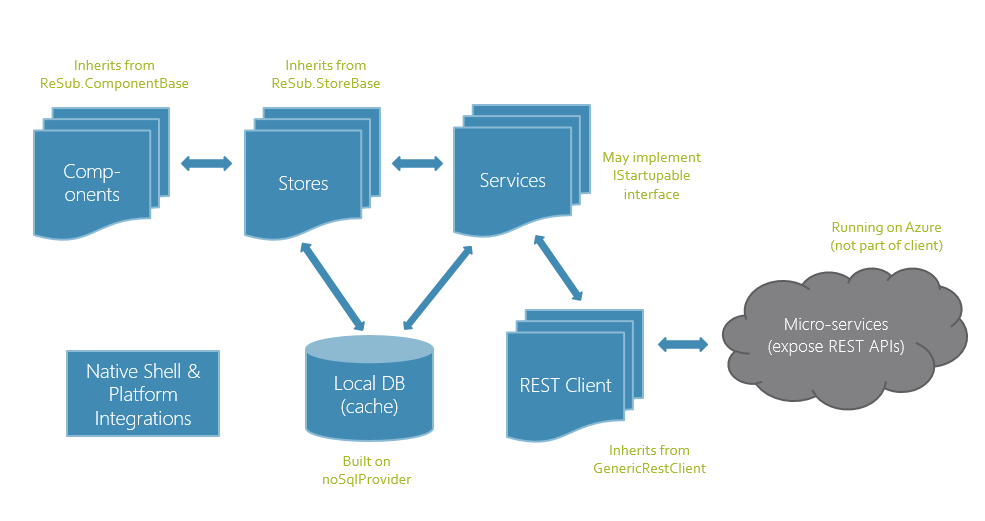

We initially tried using Flux, an architectural pattern created by Facebook engineers. We liked some of its properties, but we found it cumbersome because it required us to implement a bunch of helper classes (dispatcher, actions, action creators). State management also became hard to manage within our more complex components. For these reasons, we developed a new mechanism that we call ReSub, short for “React Subscriptions”. ReSub provides coarse-grained data binding between components and stores, and it automates the process of subscribing and unsubscribing. More details and sample code can be found on the ReSub github site.

Some stores within the app are singleton objects and are allocated — and perhaps even populated — at startup time. Others are allocated on demand and have a well-defined lifetime that corresponds to a user interaction or mode.

Caching Data Locally

Stores are responsible for maintaining in-memory data representations. We also had the need to persist data in a structured manner. Storing data locally allows the app to run in “offline” mode. It also allows for fast startup, since we don’t need to wait for data to download over the network.

For local storage, we developed a cross-platform no-SQL database abstraction. It uses the native database implementation for each platform (sqlite for iOS, indexDB for some browsers, etc.). The abstraction allows us to create and query multiple tables. Each table can have multiple indexes, including composite (multi-key) indexes. It also supports transactions and string indexing for full text searches.

Services & Startup Management

Background tasks, such as fetching new messages, are handled by modules we refer to as “Services”. These are singleton objects that are instantiated at app startup time. Some services are responsible for updating stores and saving information to the local database. Others are responsible for listening to one or more other stores and synthesizing information from those stores (e.g. notifications that are generated for incoming messages that require the user’s immediate attention).

In some cases, a service was so tightly bound to the operation of a particular store that we merged their functionality into a single module. For example, we created a ConfigurationStore to track app-level configuration settings (e.g. which features are enabled for a particular user). We could have implemented a corresponding ConfigurationService that fetches configuration updates, but we opted to implement this functionality within the ConfigurationStore out of pragmatism.

At startup time, the app needs to instantiate all of its singleton stores and services, some of which have dependencies on others. To facilitate this startup process, we created a startup manager. Each store or service that wants to be started must implement an interface called “IStartupable”, which includes a “startup” method that returns a promise. Modules register themselves with the startup manager and specify which other modules (if any) they depend upon. This allows the startup manager to run startup routines in parallel. Once a startup promise is resolved, it unblocks the startup of any dependent modules. This continues until all registered modules have been started.

Here is a startup routine that populates its store with data from the database. Note that the startup routine returns a promise, which isn’t resolved until after the async database access is completed.

startup(): SyncTasks.Promise<void> {

return ClientDatabase.getRecentConversations().then(conversations => {

this._conversations = conversations;

});

}

Communicating with the REST of the World

Skype is built upon over a dozen different micro-services that run on Azure. For example, one micro-service handles message delivery, another handles the storage and retrieval of photos and videos, and yet another provides dynamic updates of emoticon packs. Each micro-service exposes its functionality through a simple REST API. For each service, we implement a REST Client that exposes the API to the rest of the app. Each REST Client is a subclass of the Simple REST Client, which handles retry logic, authentication, and setting of HTTP header values.

Responsive Behavior

The Skype app runs on a wide variety of devices from phones to desktop PCs with large screens. It is able to adapt to screen size (and orientation) changes at runtime. This is mostly the responsibility of components at the upper layers of the view hierarchy, which change their behavior based on the available screen width. They subscribe to a store that we call “ResponsiveWidthStore”. Despite its name, this store also tracks the screen (or window) height and the device orientation (landscape vs portrait).

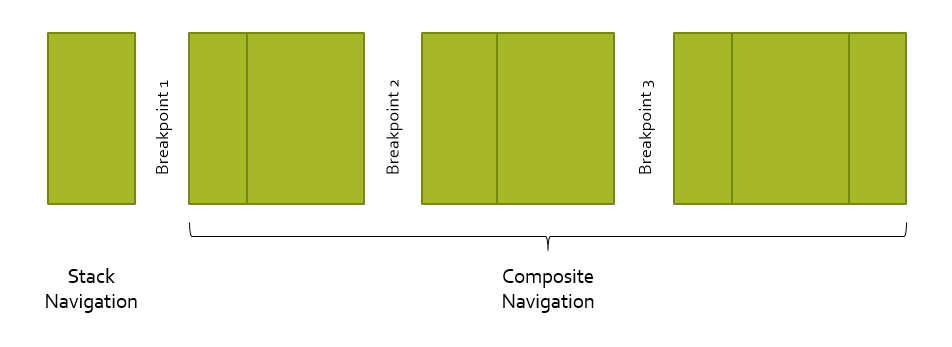

As is common with most responsive websites, we defined several “break point” widths. In our case, we chose three such break points, meaning that our app works in one of four different responsive “modes”.

In the narrowest mode, the app uses a “stack navigation” mode, where UI panels are stacked one on top of another. This is a typical navigation pattern for phones. For wider modes, the app uses a “composite navigation” mode, where panels are positioned beside each other, allowing for better use of the expanded screen real estate.

Navigation

The app coordinates navigation changes through the use of a NavigationStateStore. Components can subscribe to this store to determine whether the app is currently in “stack navigation” or “composite navigation” mode. When in stack navigation mode, this store records the contents of the stack. When in composite navigation mode, it records which panels and sub-panels are currently displayed (and in some cases, which mode they are in). This is tracked through a NavigationContext object. The parts of the view hierarchy that respond to navigation changes each have a corresponding NavigationContext. Some context have references to other child contexts, reflecting the hierarchical nature of the UI. When the user performs an action that results in a navigation change, the NavigationAction module is responsible for updating the NavigationContext and writing it back to the NavigationStateStore. This, in turn, causes the UI to update.

Here is some code that demonstrates the typical flow. We start with an event handler within a button.

private _onClickConversationButton() {

// Navigate to the conversation.

NavigationActions.navigateToConversation(this.props.conversationId);

}

The NavigationActions module then updates the current navigation context. It needs to handle both the stack and composite cases.

navigateToConversation(conversationId: string) {

let convContext = this.createConversationNavContext(conversationId);

if (NavigationStateStore.isUsingStackNav()) {

NavigationStateStore.pushNewStackContext(convContext);

} else {

NavigationStateStore.updateRightPanel(convContext);

}

}

This causes the NavigationStateStore to update its internal state and trigger a change, which notifies any subscribers.

pushNewStackContext(context: NavigationContext) {

this._navStack.push(context);

// Tell subscribers that the nav context changed.

this.trigger();

}

The primary subscriber to the NavigationStateStore is a component called RootNavigationView. It is responsible for rendering either a RootStackNavigationView or RootCompositeNavigationView.

protected _buildState(/* params omitted */): RootNavigationViewState {

return {

isStackNav: NavigationStateStore.isUsingStackNav(),

compositeNavContext: NavigationStateStore.getCompositeNavContext(),

stackNavContext: NavigationStateStore.getStackNavContext()

};

}

render() {

if (this.state.isStackNav) {

return (

<RootStackNavigationView navContext={ this.state.stackNavContext } />

);

} else {

return (

<RootCompositeNavigationView navContext={ this.state.compositeNavContext } />

);

}

}